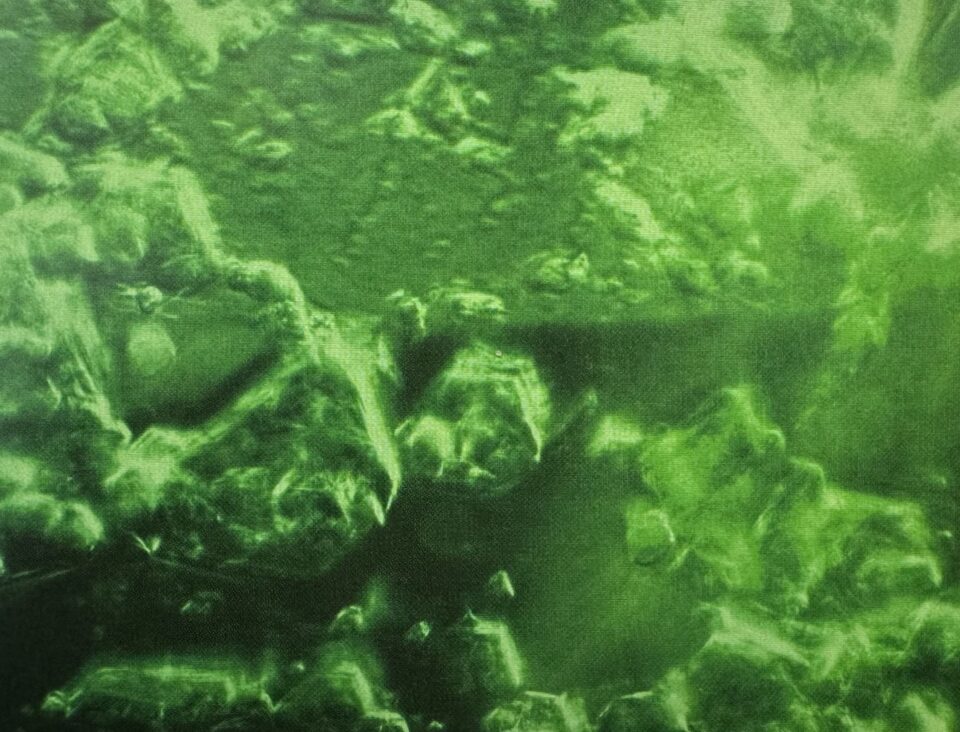

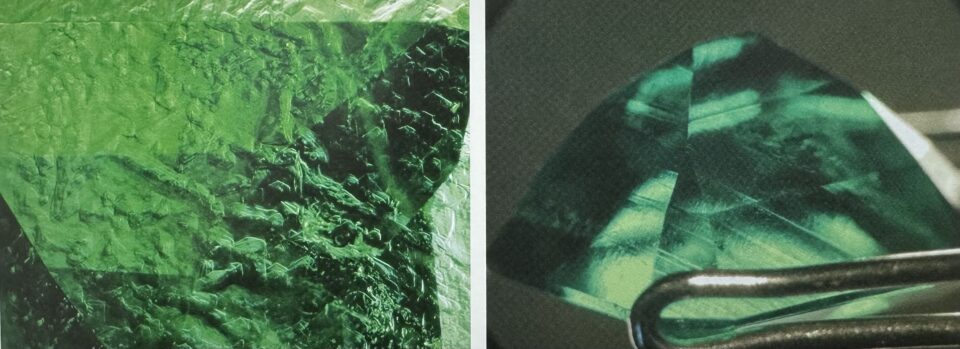

There is no better place to rediscover wonder than in a remarkable phenomenon that occurs inside the finest emeralds. That phenomenon is called gota de aceite (Spanish for “drop of oil,” pronounced “go-tuh day ah-say-tay”). A velvety interruption of the light passing through the emerald, the effect is prized by connoisseurs in the same way they value the velvety texture of a Kashmir sapphire. In both cases, the color of the stone is softened and the internal reflections are spread by numerous microscopic inclusions, reducing extinction and giving a liquid, velvety texture. Gota de aceite is associated with the Colombian emerald, and even in Colombian stones it is visible in only one in a thousand, mainly of fine quality. In six years of informal study of this phenomenon, I have only detected it rarely, personally viewing about 18 good examples, 20 moderate examples and 50 that were muted or indistinct.

The term gota de aceite is also known as the “butterfly wing effect” (efecto aleta de mariposa). Transparent irregularities in the internal crystal seem to be the result of changing and unstable conditions during emerald crystallization.

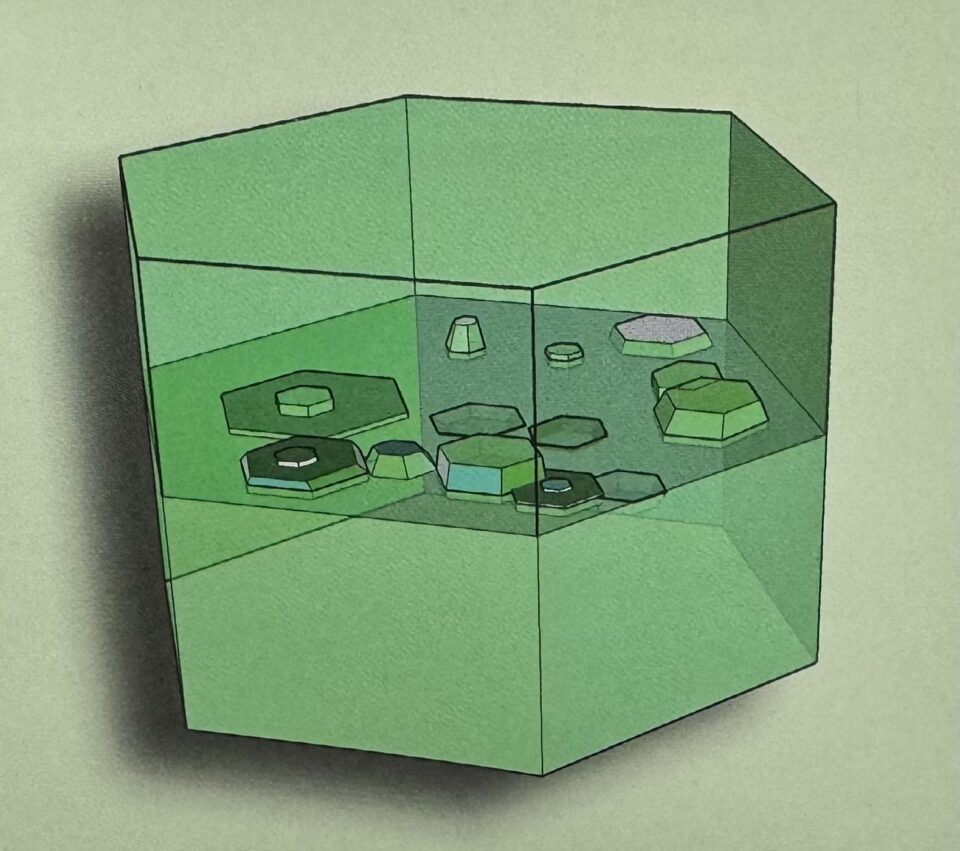

These conditions give rise to both raised hexagonal terminations as well as etched geometric depressions. After their formation, these growth structures are overgrown with more emerald. The growth structure and patterns thus formed are transparent and difluse the light within the faceted emerald in a manner reminiscent of a drop of thick oil, hence the name. Since growth structures cause the effect, there is no reason that it could not be found in emeralds from localities outside of Colombia.

This phenomenon was also referred to as calcite precipitation. It was thought to be caused by a temporary lull in the crystallization process of the emerald, allowing small grains of calcite to form that were later overgrown with emerald. The calcite theory is losing out to another explanation of gota de aceite. Close microscopic examination indicates the presence of growth structures instead of calcite, according to researcher John Koivula. He points out that the forms appear three-dimensional when viewed perpendicular to the plane of their formation, but when the stone is turned sideways, there is no space for them; they look flat. Also, no evidence of calcite was seen, either by microscopic examination or Raman spectroscopy.

In the gota de aceite effect, the etching and regrowth structures form in a plane perpendicular to the c-axis. If the emerald cutter positions this plane roughly parallel to the table of the faceted stone, it will be seen and appreciated by the viewer, increasing the emerald’s value and allure. Sadly, the effect gets wasted when the emerald’s owners and cutters do not recognize the effect and position the zone of gota de aceite to one side or perpendicular to the stone’s table. The difficulty of seeing it in the rough, along with the lack of understanding about it, is are other reasons for the great rarity of gota de aceite emeralds in the market.

Researcher and author John Sinkankas noted that beryl crystals can often have many sub-individuals included within. Since these grow along with the original crystal, they are oriented to the c-axis.

Source: Ronald Ringsrud – Emeralds A Passionate Guide